Atrial septal defect (ASD)

Overview

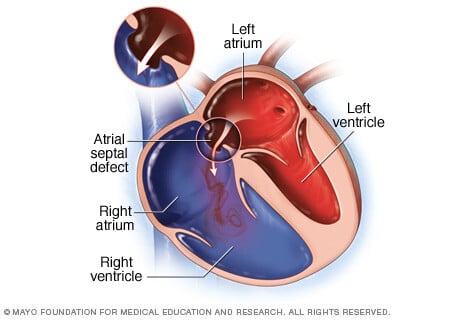

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a heart condition that you're born with. That means it's a congenital heart defect. People with an ASD have a hole between the upper heart chambers. The hole increases the amount of blood going through the lungs.

Small atrial septal defects might be found by chance and never cause a concern. Others might close during infancy or early childhood.

A large, long-term atrial septal defect can damage the heart and lungs. Surgery may be needed to repair an atrial septal defect and to prevent complications.

Types

Types of atrial septal defects (ASDs) include:

- Secundum. This is the most common type of ASD. It occurs in the middle of the wall between the upper heart chambers. This wall is called the atrial septum.

- Primum. This type of ASD affects the lower part of the wall between the upper heart chambers. It might occur with other heart problems present at birth.

- Sinus venosus. This is a rare type of ASD. It most often happens in the upper part of the wall between the heart chambers. It often occurs with other heart structure changes present at birth.

- Coronary sinus. The coronary sinus is part of the vein system of the heart. In this rare type of ASD, part of the wall between the coronary sinus and the left upper heart chamber is missing.

Symptoms

A baby born with an atrial septal defect (ASD) may not have symptoms. Symptoms may begin in adulthood.

Atrial septal defect symptoms may include:

- Shortness of breath, especially when exercising.

- Tiredness, especially with activity.

- Swelling of the legs, feet or belly area.

- Irregular heartbeats, also called arrhythmias.

- Skipped heartbeats or feelings of a quick, pounding or fluttering heartbeat, called palpitations.

When to see a doctor

Serious congenital heart defects are often diagnosed before or soon after a child is born.

Get immediate emergency help if a child has trouble breathing.

Call a healthcare professional if these symptoms occur:

- Shortness of breath, especially during exercise or activity.

- Easy tiring, especially after activity.

- Swelling of the legs, feet or belly area.

- Skipped heartbeats or feelings of a quick, pounding heartbeat.

Causes

The cause of atrial septal defect is not clear. The problem affects the structure of the heart. It happens as the baby's heart is forming during pregnancy.

The following may play a role in the cause of congenital heart defects such as atrial septal defect:

- Changes in genes.

- Some medical conditions.

- Certain medicines.

- Smoking.

- Alcohol misuse.

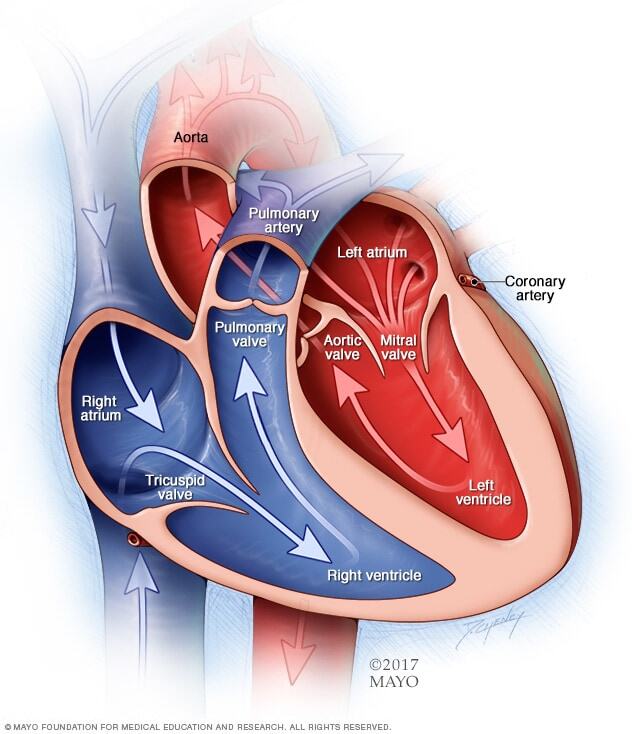

How the heart works

To understand the cause of atrial septal defect, it may be helpful to know how the heart typically works.

The typical heart is made of four chambers. The two upper chambers are called the atria. The two lower chambers are called the ventricles.

The right side of the heart moves blood to the lungs. In the lungs, blood picks up oxygen and then returns it to the heart's left side. The left side of the heart then pumps the blood through the body's main artery, called the aorta. The blood then goes out to the rest of the body.

A large atrial septal defect can send extra blood to the lungs and cause the right side of the heart to work too hard. Without treatment, the right side of the heart grows larger over time and becomes weak. The blood pressure in the arteries in the lungs also can increase, causing pulmonary hypertension.

Risk factors

Atrial septal defect (ASD) occurs as the baby's heart is forming during pregnancy. It is a congenital heart defect. Things that may increase a baby's risk of atrial septal defect or other heart problems present at birth include:

- German measles, also called rubella, during the first few months of pregnancy.

- Diabetes.

- Lupus.

- Alcohol or tobacco use during pregnancy.

- Cocaine use during pregnancy.

- Use of some medicines during pregnancy, including those to treat seizures and mood conditions.

Some types of congenital heart defects occur in families. This means they are inherited. Tell your care team if you or someone in your family had a heart problem present at birth. Screening by a genetic counselor can help show the risk of certain heart defects in future children.

Complications

A small atrial septal defect might never cause any concern. Small atrial septal defects often close during infancy.

Larger atrial septal defects can cause serious complications, including:

- Right-sided heart failure.

- Irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias.

- Stroke.

- Early death.

- High blood pressure in the lung arteries, called pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary hypertension can cause permanent lung damage. This complication, called Eisenmenger syndrome, most often occurs over many years. It sometimes happens in people with large atrial septal defects.

Treatment can prevent or help manage many of these complications.

Atrial septal defect and pregnancy

If you have an atrial septal defect and are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant, talk to a care professional first. It's important to get proper prenatal care. A healthcare professional may suggest repairing the hole in the heart before getting pregnant. A large atrial septal defect or its complications can lead to a high-risk pregnancy.

Prevention

Because the cause of atrial septal defect (ASD) is not clear, prevention may not be possible. But getting good prenatal care is important. If you were born with an ASD, make an appointment for a health checkup before becoming pregnant.

During this visit:

- Talk about current health conditions and medicines. It's important to closely control diabetes, lupus and other health conditions during pregnancy. Your healthcare professional may suggest changing doses of some medicines or stopping them before pregnancy.

- Review your family medical history. If you have a family history of congenital heart defects or other genetic conditions, you might talk with a genetic counselor to find your risks.

- Ask about getting tested to see if you've had German measles, also called rubella. Rubella in a pregnant person has been linked to some types of congenital heart defects in the baby. If you haven't already had German measles or the vaccine, get the recommended vaccinations.

Diagnosis

Some atrial septal defects (ASDs) are found before or soon after a child is born. But smaller ones may not be found until later in life.

If an ASD is present, a healthcare professional may hear a whooshing sound called a heart murmur when listening to the heart with a device called a stethoscope.

Tests

Tests that help diagnose an atrial septal defect (ASD) include:

- Echocardiogram. This is the main test used to diagnose an atrial septal defect. Sound waves are used to make pictures of the beating heart. An echocardiogram shows the structure of the heart chambers and valves. It also shows how well blood moves through the heart and heart valves.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick and painless test records the electrical activity of the heart. It can show how fast or how slow the heart is beating. An ECG can help find irregular heartbeats, called arrhythmias.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This imaging test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to make detailed images of the heart. It might be done if other tests didn't provide a sure diagnosis.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. This test uses a series of X-rays to create detailed pictures of the heart. It may be used if other tests don't give enough information to make a diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment for atrial septal defect (ASD) depends on:

- The size of the hole in the heart.

- Whether there are other heart problems present at birth.

An atrial septal defect may close on its own during childhood. For small holes that don't close, regular health checkups may be the only care needed.

Some atrial septal defects that do not close need a procedure to close the hole. But closure of an ASD isn't recommended in those who have severe pulmonary hypertension.

Medications

Medicines won't repair an atrial septal defect (ASD). But they can help reduce symptoms. Medicines for atrial septal defect might include:

- Beta blockers to control the heartbeat.

- Blood thinners, called anticoagulants, to lower the risk of blood clots.

- Diuretics to reduce fluid buildup in the lungs and other parts of the body.

Surgery or other procedures

A procedure is often suggested to repair a medium to large atrial septal defect (ASD) to prevent future complications.

Atrial septal defect repair involves closing the hole in the heart. This can be done two ways:

- Catheter-based repair. This type is done to fix the secundum type of atrial septal defects. A thin, flexible tube called a catheter is put into a blood vessel, most often in the groin. The tube is then guided to the heart. A mesh patch or plug goes through the catheter. The patch is used to close the hole. Heart tissue grows around the patch, closing the hole for life. However, some large secundum atrial septal defects might need open-heart surgery.

- Open-heart surgery. This type of ASD repair surgery involves making a cut through the chest wall to get to the heart. The surgeons use patches to close the hole. Open-heart repair surgery is the only way to fix primum, sinus venosus and coronary sinus atrial defects.

Sometimes, atrial septal defect repair can be done using smaller cuts than traditional surgery. This method is called minimally invasive surgery. If the repair is done with the help of a robot, it's called robot-assisted heart surgery.

Anyone who has had surgery for atrial septal defect needs regular imaging tests and health checkups. These appointments are to watch for possible heart and lung complications.

People with large atrial septal defects who do not have surgery to close the hole often have worse long-term outcomes. They may have more trouble doing everyday activities. This is called reduced functional capacity. They also are at greater risk for irregular heartbeats and pulmonary hypertension.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Following a heart-healthy lifestyle is important. This includes eating healthy, not smoking, managing weight and getting enough sleep. If you or your child has an atrial septal defect, talk to your healthcare team about the following:

- Exercise. Exercise is usually OK for people with an atrial septal defect. But if ASD repair is needed, you might have to stop certain activities until the hole in the heart is fixed. Ask a healthcare professional what type and amount of exercise is safest.

- Extreme altitude changes. Extreme changes in location above or below sea level may cause complications in people with an unrepaired atrial septal defect. For example, there's less oxygen at higher altitudes. The lower amount of oxygen changes blood flow through the lung arteries. This can cause shortness of breath and strain the heart.

- Dental work. If you or your child recently had an ASD fixed and need dental work, talk to a healthcare professional. You or your child may need to take antibiotics for about six months after repair surgery to prevent infection.

Preparing for an appointment

A doctor trained in heart problems present at birth usually provides care for people with an atrial septal defect. This type of healthcare professional is called a congenital cardiologist.

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Make a list of:

- Your or your child's symptoms, and when you noticed them.

- Important personal information, including major stresses, recent life changes and any family history of heart problems present at birth.

- All medicines, vitamins or other supplements being taken. Include the dosages.

- Questions to ask during your appointment.

For atrial septal defect, questions to ask might include:

- What's the most likely cause of these symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What tests are needed?

- Is the atrial septal defect likely to close on its own?

- What are the treatment choices?

- What are the risks of repair surgery?

- Are there any activity restrictions?

- Are there brochures or other printed material I can have? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional is likely to ask questions, including:

- Do you or your child always have symptoms or do they come and go?

- Do symptoms get worse with exercise?

- Does anything else seem to make the symptoms worse?

- Is there anything that seems to make the symptoms better?

- Is there a family history of congenital heart defects?